Leonardo Da Vinci was, of course, both figuratively and literally a Renaissance man who was a certified genius in every field from sculpting to inventing. He is perhaps most famous as a painter, however; certainly nothing else connected with Da Vinci has entered into the public consciousness quite as deeply as his iconic portrait popularly known as the Mona Lisa. Leonardo Da Vinci’s lasting contribution the art of painting was his conception of painting as a science form rather than strictly an art form.

Leonardo Da Vinci approached painting from a mathematical perspective, inventing a system that allowed him to create the illusion of depth and distance. The result is what came to be known as aerial perspective. It is also known as atmospheric perspective because it gives a painting the illusion of distance based on atmospheric qualities. As developed by Da Vinci this technique extends well beyond mere perspective, however, as he uses it to imbue his subjects with a sense of harmony and balance.

For instance, his fresco representation of Christ’s last supper with his disciples becomes far more than just a pictorial retelling of a Biblical event. Leonardo Da Vinci engages in atmospheric perspective to create a sense of spatial illusion that turns the dramatic events that Bible tells us unfolded during the meal into a psychological drama almost as full of action as a passion play. It is hardly by accident that The Last Supper plays such a large role in the novel and film The Da Vinci code. Through the simple of use composition, balance and lighting, Da Vinci creates a large scale mini-drama in which the attention of the viewers can never stay focused on any one particular area for long.

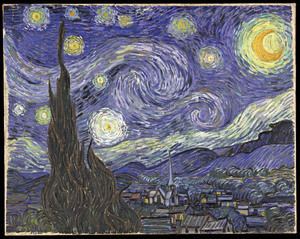

Equally revolutionary was Da Vinci’s creation of the technique of sfumato, which involves creating several layers of color on a painting in order to enhance the perception of depth and form. Da Vinci’s most famous accomplishment as a painter derives much of its mystery as a result of the sfumato application. The Mona Lisa’s enigmatic expression has been a source of contention among both art experts and laymen for centuries. Is the look on her face one of happiness, sadness or might it even contain just a hint of contempt?

It is difficult to determine for sure, in part because of the technique that Leonardo used to blur the contours of the painting so that the transition is blurred from plane to another within the frame. The Mona Lisa, as a result, stands in stark contract to The Last Supper in that he has replaced the psychological certainties that exist in the huge fresco-where the viewer has little if any trouble determining the states of mind of any of the figures-with the world of ambiguity that lives inside the tiny figure of La Giaconda. His use of sfumato serves to disguise the subject by blurring the edges and creating an overall fuzzy quality to the painting. The boundaries that are so sharp in The Last Supper merge into each other in the Mona Lisa and take with them any real opportunity for definition. And yet, the very same technique that limits the ability of the viewer to precisely define her also makes her more human. There is a warmth and fleshly quality to the Mona Lisa directly due to the sfumato technique paradoxically makes her both a little more real while at the same time rendering her eternal.

Leonardo Da Vinci carved out a legacy for himself as the ultimate example of what a human being can is able to accomplish. He was by turns a scientist and an artist, both coldly mechanical and sensually attuned with nature. Perhaps nowhere did the oppositional nature of Leonard Da Vinci’s interests come together to achieve a singular perfect than in painting. By approaching the art of painting as a form of science, and applying all his great mathematical genius to the act of applying brush to canvas, Leonardo Da Vinci essentially revolutionized the art of painting. As a leading member of the Renaissance revolution, he was instrumental in turning the focus of art away from strictly realistic portraiture and staid representations of religious figures and events into a vibrant art.